TOM ALLEN - His Story

(annotated to original sources)

1. VOLUNTEERING FOR

SERVICE WITH NELSON

Tom Allen

was a native of Nelson’s own home area of Burnham in north Norfolk.(17,18,19)

He was

baptized Thomas Allen on

Nelson, who

once remarked that ‘a Norfolk man was as good as two others’(25) sought local men from Burnham to join him for his command of HMS

Agamemnon at the beginning of the war with France. Tom joined as a 21 year old

volunteer on

It was said

that ‘from his earliest years’ Tom had been ‘in the service of the Nelson

family’(4) but he was not personally known to

Nelson’s wife Fanny before the voyage, as Nelson in a letter to her referred to

him not by his name but simply as a ‘Norfolk ploughman’. (11)

His grading

as an Ordinary Seaman, not a Landsman, ought to suggest some previous

experience at sea. It is possible that as a man on the north

Nelson

already had a long-established personal sailor-manservant appointed for the

campaign, Frank Lepée. Frank was almost part of his family, having

served Nelson for many years in the

It was to

be a long campaign in the

2. TOM APPOINTED NELSON’S

SERVANT/ BATTLE ST

VINCENT

Tom was a

rough country character, without education, clumsy and outspoken, and

ordinarily would not have been considered for the post. (1,4 ) But in the years that followed--the

continuing strenuous and unrelenting Mediterranean campaign--he and Nelson were

to establish a special relationship. It seemed that Tom possessed those

qualities that Nelson always valued above all others from himself and his

men—an unquestioning loyalty and a strong sense of duty.

First

mentioned in Nelson’s letter to Fanny on

It was

about this time, off

It is

universally agreed the two great men never did meet- and the writer of the

article wondered if Tom might have been mistaken- but the time and place for

such a historic meeting-- before either was famous-- are not implausible. (5)

After years

of vainly seeking out his enemy for a major confrontation, Nelson at last

secured his first famous victory at the Battle of St Vincent on

Tom was one

of the sailors fighting at Nelson’s side but he fell badly wounded. According

to his later pension record, the wound was in his ‘Privates’. (1,4,18)

He

recovered-- though perhaps left disabled with a walk ‘like a heavily laden ship

rolling before the wind’(1,3) There was no respite and no return to

Five months

later Nelson again led an attack barely surviving an action off

3. BATTLE OF THE NILE

The sudden

promotion Tom had gained three years before was now confirmed on their return

to

Tom now

also had money which was substantial enough to be deposited with Nelson’s own

agents, Marsh and Creed. (12)

It was not

long before they were back at sea for a new campaign in the Mediterranean on

board HMS Vanguard. (17)

Nelson this

time had a ‘retinue’ as a Rear-Admiral including Tom, aged 26. Letters back and

to between Nelson and Fanny refer to Tom’s part in the domestic preparations

for the voyage. (11,12)

On 1 Aug

1798 Nelson won his second great victory at the Battle of the Nile.

Tom again

took his turn in the action, being as usual stationed at ‘one of the upper-deck

guns’,(4) but his providential contribution to this

battle was an inadvertent one.

Before

action commenced Nelson’s hat had been too loose-fitting. Tom had sewed in a

special pad and this saved Nelson’s life when he took a shot to his head- so

serious Nelson believed himself mortally wounded. (5)

4. LADY HAMILTON

After the

victory, which secured for Britain control of the Mediterranean, Nelson

received congratulations from one and all. None more so than from Emma, Lady

Hamilton, at Naples, where her husband Sir William Hamilton was ambassador to

the court. Her devoted praise turned into a love affair.

On 26 Dec

1798 the court had to flee Naples to Palermo and in the worst storm Nelson

could remember Tom helped Emma care for the royal family unused to such

hardship. (12,13)

At

He became

so involved that he could later joke that ‘he might have married either of the

princesses, had he been so minded’. (4)

This was

the time of the famous moment he refused to kneel before or kiss the hand of the King of Naples, when he came on to the

Foudroyant for a royal visit. Instead Tom heartily shook his hand with the

rough greeting ‘How d’you do, Mr King’. As for not kneeling Tom explained, ‘he never

bent his knee but in prayer and he feared that was too seldom’. (1,3)

He was

similarly out of line on 14.2 1800 at a St Vincent anniversary dinner, when he

joined in conversation as if on equal terms with one of the guests, Captain Coffield, asking after the health of a shipmate. Nelson

dismissed him from the cabin for his ‘impudence’, though only to accept Tom

interrupting later to suggest he had drunk too much wine, and thus ‘the

greatest naval hero of the day was led from his own table by his faithful and

attached servant’. (1,2,3)

Tom never

felt unequal in his elevated surroundings. He later reminisced that ‘had he but

been a scholar, he might have been as high as Sir Thomas Hardy or any of the

rest of them’.(5)

He was more

than once threatened with dismissal—‘a threat so often used that it was at

length disregarded’. Said Tom on one occasion-‘He ma’ talk about turning me awa’, if he likes, but you know he awes me thirty pounds

and more’(8,26)

In the end

Tom’s loyalty and attentiveness were more important to Nelson than his

unruliness. ‘Next to Lady Hamilton, Tom Allen possessed the greatest influence

with his heroic master,’ witnessed Parsons (1,3)

Another

story was told at this time of how, when the Foudroyant

steered too close to the coast of Malta and cannon-fire began to threaten the

decks, Tom ‘interposed his bulky form between those forts and his little

master’. (1,3,4).

When a

coffin was presented to Nelson made from a French wreck from the Battle of the

Nile- the mainmast of L’Orient- Tom insisted it be

removed from his cabin, as he said it would bring bad luck. (10,20,26). “It always puts me in mind of a corpse”, said

Tom. (9a)

Meanwhile

Nelson and Fanny were still exchanging letters and one of Fanny’s included a

love-letter for Tom himself. (11) Tom’s clumsiness was also

mentioned- he had overset the ink’, as he busied himself in Nelson’s cabin. (11,13,14,15)

5. RETURN TO ENGLAND/

BATTLE OF COPENHAGEN

In the

middle of 1800, Nelson was forced finally to return to England. He took a

land-route through Europe, which became an almost regal celebration. Emma, now

pregnant, accompanied him.

Tom is

mentioned once as warning Nelson not to drink too much champagne. (21)

Once they

were back home, the separation from Fanny began, as Nelson spent as much time

as he could with Emma. While Nelson and Emma were being entertained for

Christmas at Fonthill, Tom took the opportunity to

return to Norfolk to marry Jane Dextern at Docking on

31 Dec 1800. (19) Jane was the sister of Elizabeth Dextern, who had married Tom’s brother William Allen some

years earlier.

Tom had

more money- a draft for £95 just given to him, (12) as well as his share of the 100

ounces of silver the King of Naples had donated to Nelson’s servants. (10)

Soon Tom

would also be mentioned in Nelson’s new Will of 16 Mar 1801, to be given £50

and all his ‘cloaths’. (12)

Now a

Vice-Admiral, Nelson joined HMS San Josef on 17 Jan 1801 in readiness for his

next great campaign in the Baltic. (17)

Before

setting off, Tom was recorded to have accompanied Nelson on a furtive visit to

see Nelson and Emma’s new baby daughter, Horatia,

being cared for by a Mrs Gibson (22). Later in life Tom would be quizzed

on what he knew of this secret birth.

On 2 April

1801 Nelson fought and won his third famous victory -the Battle of Copenhagen.

Once again Tom played his part by insisting at the pre-battle conference the

night before that Nelson took rest. An eye-witness Hon. Col. Stewart noted that

Tom ‘assumed much command on these occasions’. (10,20)

It was a battle

Tom later was reluctant to talk about, for reasons he did not explain. (4)

After the

battle Nelson and Emma took a holiday at Staines. Emma received there a poem

from Lord William Gordon, which included a mention of Tom’s bravery and

recording also how before Copenhagen Tom had taken special care of Emma’s

portrait that took pride of place in Nelson’s cabin. (13)

“Nor, by

our Muse shall Allen be forgot

who for himself nor bullets fear’d nor shot…”

6. AT HOME IN MERTON

In August

1801, when fear of an invasion by Napoleon was at its height, Nelson and Tom

took to sea again, defending the Channel coast. (17)

There is a

firm record at this time of Nelson seriously losing his temper with Tom. A case

containing all Nelson’s papers and £200 was mislaid. It was soon recovered but

Nelson claimed that Tom ‘never says truth’. ‘He will one day ruin me by his

ignorance, obstinacy and lies’.(13)

Despite

this, Tom was to be part of the new household that Nelson and Emma were

establishing at Merton. Peace with Napoleon was being negotiated and Nelson was

looking forward to his retirement.

Tom’s new

wife Jane had come down from Norfolk and she was to be the dairymaid. (11)

Jane got on

well with Emma pleasing her on one occasion by remarking that Emma and William

Nelson’s wife were both ‘like so many Venuses’.(23)

In the last

months on board, Tom’s letters to Jane were being enclosed with Nelson’s

letters to Emma.(12,13,15)

As a

farewell present Captain Sutton gave Tom a goat. (15)

At Merton,

Tom became butler for a short time and in one of his reminiscences Lt. Parsons

describes a visit he made to Merton to request a favour from his old captain.

Tom and Emma conspired to help him gain Nelson’s cooperation. (1,2)

On 9 Feb

1802 Tom, now 30 years old, left Nelson’s service, returning home to Norfolk

with Jane to start a family. This meant he had to be discharged from the Navy

and Nelson wrote accordingly to Captain Sutton. (10,17) Later

that year their first son was baptized at Fakenham—Horatio

Nelson Allen- on 10 October. (19) It was said Nelson was his godfather. (4)

Two drafts

were paid to Tom, £100 on

However all

the sources agree that the two men quarrelled at some point. (4,7)

This

appears to be the time of the quarrel as shown by the next mention of Tom, two

years later when Nelson was back at sea.

In a letter to Emma from his ship on 13 Oct 1804, Nelson reported that

Tom-“poor foolish man”- had written for a reference. (15) Similarly on 30 Aug 1805, when briefly back at

Merton, Nelson responded to another request for a reference on Tom received

from Rev Glasse- Tom had applied to be his steward-

and Nelson’s language is more critical-

Tom ‘did not make a very grateful return’ and ‘would not be able perform

such a service well’ (16)

7. TOM MISSES THE BATTLE

OF TRAFALGAR-21OCT 1805

The usual

account in the original sources was that Tom became reconciled to Nelson. So

reconciled, he was intended to be at Trafalgar but was left behind on shore

accidentally when Nelson left hurriedly to rejoin HMS Victory on 14 Sept 1805.

It states ‘Tom was left at Merton with orders to join his master as soon as

possible’ but ‘the last ship had sailed before his arrival in Portsmouth’. (4,5,6,9)

However Tom

was never on the Victory Ship’s Muster (17), and given the now known letter to Rev.Glasse –only recently published--, the usual account

seems most unlikely. The letter was dated only two weeks before setting sail

and would have required a complete change of heart by Nelson within only days

of his writing it.

Another

source is worded differently. It says that ‘on his Lordship’s obtaining the

command of the Mediterranean, Tom Allen said that his Lordship wrote to him to

go with him again.’ Tom, it went on, missed Nelson leaving London, missed him

again at Portsmouth, was offered a place on the next passage, but changed his

mind and returned to his wife, Jane. (8)

This makes

more sense because the date would be much earlier-May 1803- when Nelson first

sailed and would explain Nelson feeling let down, hence the problem he had

giving Tom a reference.

(In another

copy of this source there is an additional footnote stating ‘on very good

authority’ that Nelson did not write to Tom.) (7)

Finally

there is a memory in Tom’s family of a critical letter from the Admiralty,

implying Tom missed Trafalgar due to intoxication. (16a)

Tom was

certainly eager to return to sea- this is proved by his subsequent rejoining

the Navy in 1809.

But his

reluctance to leave Jane is understandable—she had a second son baptized at Fakenham on

The

conclusion seems to be that Tom made some effort to be with Nelson for his last

campaign-though in 1803 rather than 1805- either with or without Nelson’s

knowledge- but he did not see it through.

The popular

account, depicting Tom left on the quayside as Nelson sailed to his death,

fitted the earnest debate in the sources as to whether Nelson died only because

Tom failed to be with him at Trafalgar. In earlier battles Tom had insisted on

Nelson wearing modest uniform. On the deck of the Victory at Trafalgar, wearing

dress uniform instead, Nelson was more conspicuous and, in the hour of his

greatest victory, fell mortally wounded to a sniper’s bullet. (All)

Tom later said “I never told anybody that if I had been there, Lord

Nelson would not have been killed: but this I have said, and say again, that if

I had been there, he should not have put on that coat. He would mind me like a

child”.(9a)

8. TOM’S LATER LIFE

His family

(two boys) now complete, Tom did go back to sea, four years after Trafalgar,

volunteering on 26.11.1809 for HMS Circe. He served just over two years off the

coast of Spain in the Peninsular War, before being invalided out on 14 March

1812. (17,18)

The next we

hear of Tom is back home in Burnham—about 1817- when he became a personal

servant to Sir William Bolton—Nelson’s close relative. (4,5,7,8,9) It was while he served the Boltons

that Nelson’s daughter Horatia came to live with

them. Horatia married the local curate Rev. Philip

Ward and started a family. (Tom’s niece, Bet Allen, was around this time

appointed the nursemaid (24). She remained so until her death in

1860, when Horatia provided a headstone in gratitude,

still standing in Burnham Sutton churchyard).

Having

started her family Horatia began to research her

mysterious past and took the opportunity to question Tom about what he knew of

the scandal of her birth.

Horatia

had always known Nelson to be her father but never publicly accepted Emma to be

her mother. Later Emma’s parentage was not questioned but at the time there was

much public controversy.

If there

was one person who could help it should have been a close servant such as Tom

Allen, but his contribution simply added further mystery. He said his memory

was of a quite different pregnant woman enquiring of Nelson at the time and

that he had recognized her to be the sister of a merchant they had met at

9. PENSIONER AT GREENWICH

When Sir

William Bolton died in 1830, Tom was aged 58 and facing hardship. A local

Norwich gentleman Page Nicol Scott, an ex-naval

surgeon, took up his cause, writing to both Sir Thomas Hardy and Sir William

Beatty to arrange Tom’s admission as an In-Pensioner at Greenwich Naval

Hospital. (4) Perhaps Scott had been a friend of

Sir William Bolton but there was also another connection, -- Scott, Nelson and

Tom had been freemasons. (8)

On 19

October 1831, Tom was duly admitted to Greenwich and employed as a gardener by

the Lieutenant-Governor Sir Jahleel Brenton. (4)

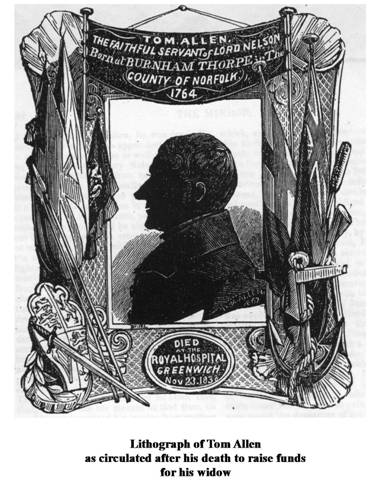

He was aged

59 but his entry record stated he was much older at 66/67 years old. All

subsequent Greenwich records, including his memorial stone and the memorial

card above these notes assumed this higher age. It is not known if this was a

simple error, or a deliberate way of easing in his entry as an In-Pensioner. (18)

On 19 June

1837, Sir Thomas Hardy himself became governor and Tom was promoted to Pewterer. This gave him a handsome salary of £65 p.a. and

also gave him an apartment in the West Hall for himself, his wife Jane and his

granddaughter, Susan. (4,18)

Nelson’s

memory had always been revered since Trafalgar but around this time there was a

particular revival of interest, especially seeking the reminiscences of the

dwindling band of those who had sailed with him. Tom became something of a

celebrity and his life was used, broadly, as a model for a popular novel of the

day- Captain Chamier’s ‘Ben Brace, the Last of the Agamemnons’. (1,3,4,5,6,7)

Tom was

also employed by Hardy for a particular task in September 1837 in attending an

enquiry at Southwark to identify some jewels of Nelson that had been deposited

by Lady Hamilton’s executor. (4)

When Tom

died

10.

SOURCES

Much of the

original source material was written around the time of Tom’s death in 1838.

It was 30

years since Trafalgar and there was a growing appetite to record memories of

Nelson’s exploits from the dwindling band of those who had sailed with him.

1. Nelsonian

Reminiscences (1843)—Lt. G.S.Parsons

Republished

as I Sailed with Nelson (1973), Lieutenant Parsons was a young

midshipman on HMS Foudroyant 1799-1800 and was an

eye-witness to many colourful stories of Tom’s close relationship to Nelson and

Lady Hamilton. His reminiscences had appeared earlier in

2. Metropolitan

Magazine Vol 19 1837

and

3. Metropolitan

Magazine Vol 28 May-Aug 1840.

The other

major tribute to Tom is contained in an Appendix to

4. 1840

Edition of Clarke & M’Arthur’s The Life and

Services of Horatio Viscount Nelson

This

contains some of the earlier Parsons material and the Appendix is then itself

reproduced in Parsons (1843)

Much of the

above was repeated in other publications but other material is added in:-

5. United Service Journal

& Naval & Military Magazine Feb 1836

6.

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction 9 Nov 1839

7.

United Services Journal Oct 1839

8.

Freemason’s Quarterly Review 31 Dec 1839

9.

Extracts from the Norwich

9a.

Notes and Queries- Nov 15 1856 and July 16 1864 .

These were

reminiscences of the Catholic writer Dr F.C. Husenbeth,

priest near Sir William Bolton’s final home at Costessey,

who “ met Tom almost every day.. and got into chat

with him about his brave and noble master”.

http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/ilej/image1.pl?item=page&seq=6&size=1&id=nq.1856.11.15.2.46.x.384

http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/ilej/image1.pl?item=page&seq=1&size=1&id=nq.1864.7.16.6.133.x.60

Earlier

there were many mentions of Tom in Nelson’s own correspondence, published in:-

10

The Dispatches and Letters of Vice-Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson- Nicolas (1845)

11.

Nelson’s Letters to his Wife and Other Documents—Naish

(1958)

12. The Hamilton & Nelson Papers- Morrison

(1893/4)

13.

Memoirs of the Life of Vice-Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson- Pettigrew (1849)

14.

Faber Book of Letters, ed. Felix Pryor

15.

Letters of Lord Nelson to Lady Hamilton- Anon (1814)

16.

Eastern Daily Press 10.11.1995 and the Times 31.10.1995, etc.

16a.

Eastern Daily Press 1.1.2005

Official

Records are:-

17.

Ship’s Musters at PRO Kew

18.

Greenwich Hospital Records at PRO Kew

19. Parish Registers

Nelson

biographies have found other material:-